(clj 12) Core concepts of functional programming with Peg Thing

Chapter 5 of “Clojure for the Brave and True” explores two core concepts of functional programming: pure functions and immutable data structures. It wraps up with walking you through the code1 of a game called “Peg Thing”2, which uses “everything you’ve learned so far: immutable data structures, lazy sequences, pure functions, recursion - everything!”

So what is this Peg Thing?

For a full description and the code of Peg Thing, you can follow the links in the paragraph above. In this post I’ll only share what’s relevant to describe what I learned about functional programming through Peg Thing.

The code of Peg Thing consists of four parts:

- create the board, which contains 11 functions and 1 variable,

- represent board textually and print, which contains 7 functions and 5 variables,

- interaction, which contains 9 functions, including the

-mainfunction, - move pegs, which contains 8 functions.

There are also calls to 3 functions with side effects: println, read-line, and System/exit.

A function call graph

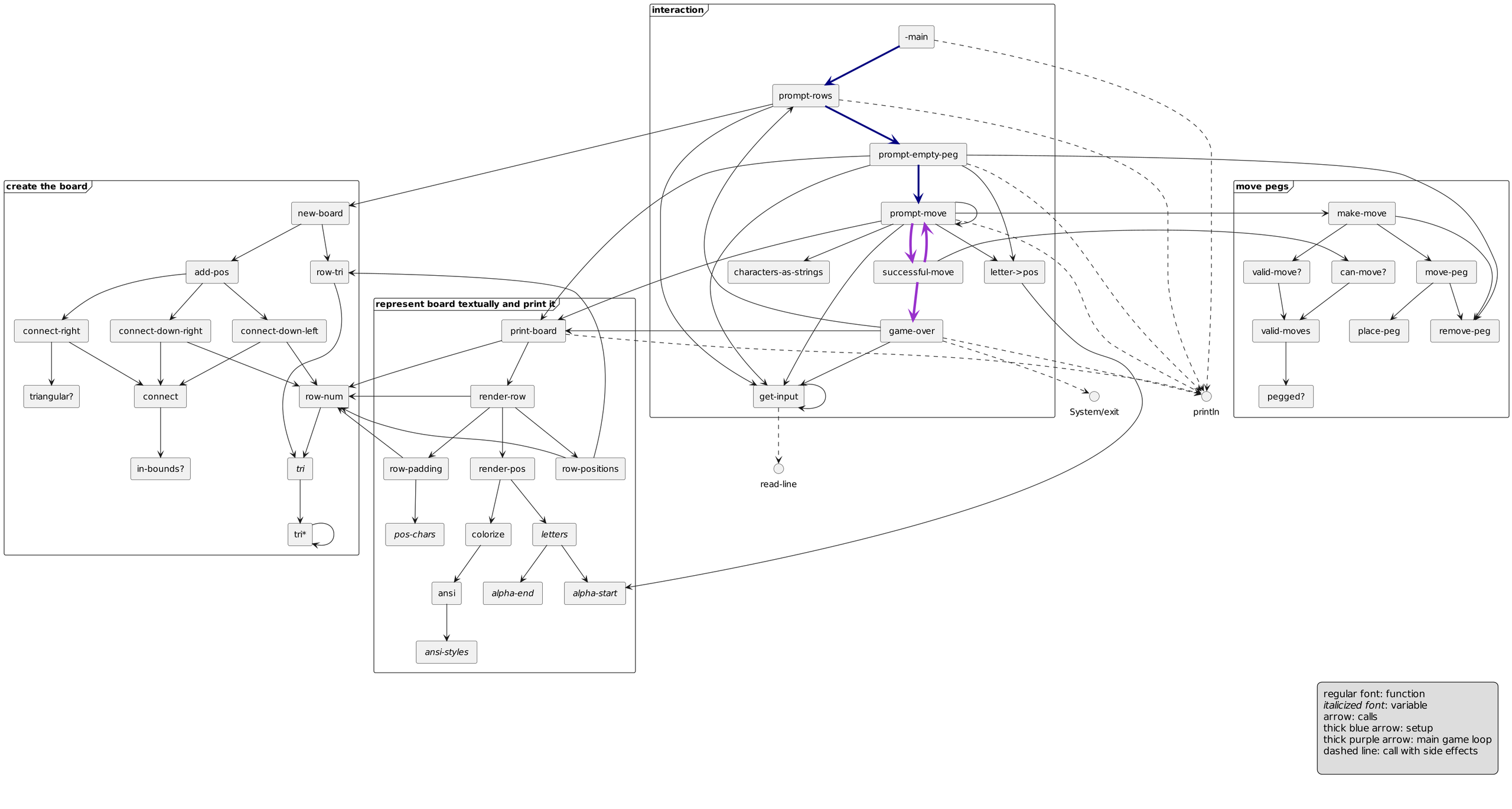

Since that’s quite a lot of functions and variables, I made a function call graph:

Every box is a function (normal font) or a variable (italicized).

Every arrow is a call from a function or variable to another function or variable.

The blue arrows from -main to prompt-rows to prompt-empty-peg to prompt-move is what sets up the game. The purple calls back-and-forth between prompt-move and successful-move are the main game loop, ending eventually with a call to game-over. The dashed lines are the calls to the three functions with side effects.

Limits of the functional call graph: sequence

One important thing to note is that the graph does not communicate the order in which one function calls other functions. For example, here’s the code of prompt-rows:

|

(defn prompt-rows

|

|

[]

|

|

(println "How many rows? [5]")

|

|

(let

|

|

[rows (Integer. (get-input 5))

|

|

board (new-board rows)]

|

|

(prompt-empty-peg board)))

|

Let’s walk through this code line-by-line:

-

defn prompt-rowstells Clojure we want to define a function calledprompt-rows. -

[]are the input parameters of our function, so in this case none. -

(println "How many rows? [5]")prints the text in double quotes to the terminal. -

letallows us to define to two variables in the current scope,rowsandboard. -

rowsis the number of rows entered by the user, as an integer. -

boardis a new board with the number ofrowsspecified, returned by thenew-boardfunction. -

(prompt-empty-peg board)calls theprompt-empty-pegfunction withboardas argument.

So while the function call graph shows four outgoing arrows from prompt-rows, the one to prompt-empty-peg is the most important one. To provide that call with its argument, however, we need the calls to println, get-input, and new-board.

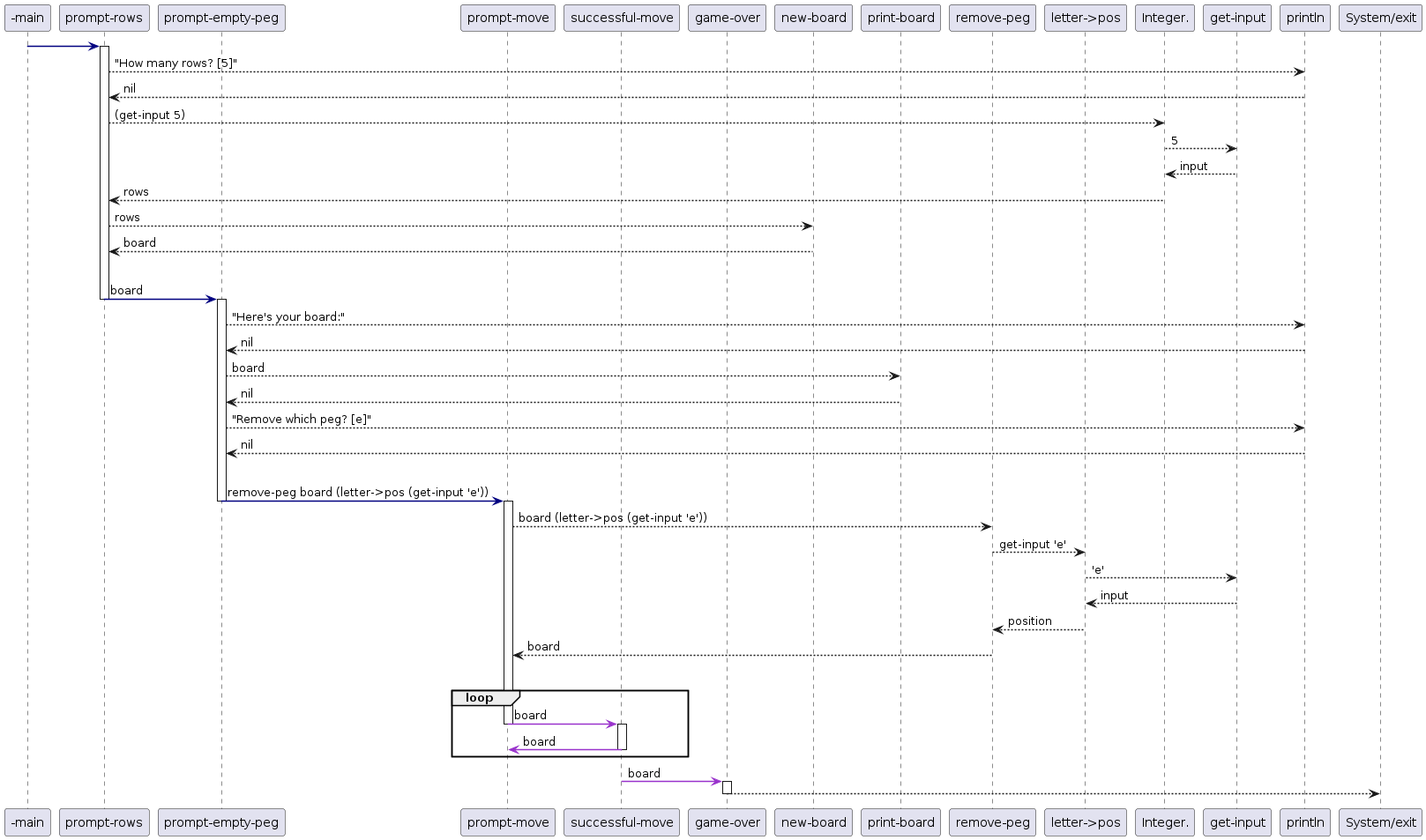

When I realized this, I tried to make a sequence diagram, but got messy really quickly. Some time later I made a second attempt with more success. It shows the board setup with prompt-rows, prompt-empty-peg, and prompt-move in detail. For context I also added the main game loop of Peg Thing: prompt-move, successful-move, and game-over.

What does Peg Thing teach about functional programming?

Before going into Peg Thing, chapter 5 of the book explains pure functions and immutable data.

A pure function is a function that (1) returns the same result if given the same arguments, and (2) does not cause any side effects. The advantage of a pure function is that if you know what arguments go into the function, you’ll know what the function will return and you know it won’t do anything else. So it allows you to think about the function without having to worry about anything outside of the function.

This is also where immutable data comes into play. Being allowed to change data (think about things like state and attributes here) is being allowed to create side effects. By not allowing this, i.e. by having immutable data, Clojure avoids these.

Function composition

That does lead to the question: if you can’t change data, then how do you get anything done? The answer is function composition: combining functions so that the return value of one function is passed to another.

You can see this in both the call graph and the sequence diagram of Peg Thing. The pyramid shape of “create the board”, “represent board textually and print it”, and “move pegs” show how Peg Things consists of functions calling functions calling functions. There’s not a big main function, doing things step-by-step. It’s even clearer in the sequence diagram where we can see prompt-empty-peg calling (prompt-move (remove-peg board (letter->pos (get-input "e")))), which goes four levels deep.

But what about all the boards?

Another thing you may have noticed in the sequence diagram, is that board seems to get passed around a lot. It certainly did confuse me initially: if the board changes during a game of Peg Thing and board gets passed around, how is that immutable data?

Going through the code made me realize that this question came from my non-functional programming intuitions. It’s not the case that board gets passed around and changed. A lot of functions in Peg Thing do require a board as argument and return a thing that’s a board. It’s however not true that a single board variable gets passed into the function as argument and that same variable but changed, comes out as the return value.

As an example, look at the following three functions:

(defn place-peg "Put a peg in the board at given position" [board pos] (assoc-in board [pos :pegged] true)) (defn remove-peg "Take the peg at given position out of the board" [board pos] (assoc-in board [pos :pegged] false)) (defn move-peg "Take peg out of p1 and place it in p2" [board p1 p2] (place-peg (remove-peg board p1) p2))

move-peg calls place-peg with the return value of remove-peg as one of its arguments. Also good to mention here, is that Clojure doesn’t have an explicit “return” keyword. A function always returns the result of the last expression it evaluates3. So move-peg will return whatever the result is of (place-peg (remove-peg board p1) p2). place-peg returns whatever assoc-in returns, which according to its docs is “a new nested structure”. remove-peg behaves similarly to place-peg.

Immutable data and function composition go together

All of this means, that when move-peg is called with a board argument, remove-peg will take that board and return a new one. Then place-peg uses that board and returns another new one, which is returned by move-peg. So while there are lots of functions in Peg Thing that require a “board”-like data structure, there is not a single board used throughout the program. Immutable “board”s are created as the program runs and its functions are called.

To reiterate, what Peg thing does not do (switching to Python syntax here), is re-using the same variable :

board = new_board(rows) board = prompt_empty_peg(board) board = prompt_move(board) board = prompt_move(board)

It also doesn’t do this, i.e. having a main function that keeps initializing new variables:4

full_board = new_board(rows) starting_board = prompt_empty_peg(full_board) board_1 = prompt_move(starting_board) board_2 = prompt_move(board_1)

Rather, it uses -main, prompt-rows, prompt-empty-peg and a first call to prompt-move to set up the board. Then there are two mutually recursive functions, prompt-move and successful-move, while playing the game, until successful-move decides there are no more valid moves and calls game-over.

Reflection

To me, that is the most interesting aspect of Peg Thing: immutable data and function composition go together. There is not some core entity (whether that’s a function or a class) that owns both the main logic and main data of your program. Instead, there’s a tree of functions, each being called with some piece(s) of data as arguments, returning a different piece of data.

It makes me curious to read and write more Clojure, since it’s the first time while working my way through the book, I’m not just intrigued by how Clojure’s syntax is different from what I’m used to, but also by how you design your programs differently.

Two other interesting things in Peg Thing’s code

let is surprising

The Clojure docs say that let‘s syntax is (let [bindings*] exprs*) and that it “evaluates the exprs in a lexical context in which the symbols in the binding-forms are bound to their respective init-exprs or parts therein.” I did not find that particularly helpful.

The Brave Clojure-book does a better job by saying:

So,

letis a handy way to introduce local names for values, which helps simplify the code.

What surprised me about it, is that let doesn’t just let you assign a local name to a variable. It lets you assign a local name to what’s returned by an expression and then use that return value within the let. For example, in Peg Thing, there’s the add-pos function:

(defn add-pos "Pegs the position and performs connections" [board max-pos pos] (let [pegged-board (assoc-in board [pos :pegged] true)] (reduce (fn [new-board connection-creation-fn] (connection-creation-fn new-board max-pos pos)) pegged-board [connect-right connect-down-left connect-down-right])))

The let [pegged-board (assoc-in board [pos :pegged] true)] makes the return value of (assoc-in board [pos :pegged] true) available as pegged-board, which is then used in the reduce function. So, you can ‘hide’ quite some logic in a let.

triangular? is cool

As you can see in the call graph, there are quite some functions whose name ends with a question mark, for example triangular? and valid-move?. I think it’s great it’s possible to use question mark like this and prefer it over alternatives like is_triangular.

Turns out it’s not only possible, but it’s part of the Clojure style guide and they’re called predicate functions. I also found a blog post by vlaaad about “Question marks in Clojure” going a bit deeper into the usage of question marks in Clojure.

-

If you want to run it with

lein repl, make sure to update the Clojure version inproject.clj. I got the error message “As of 2.8.2, the repl task is incompatible with Clojure versions older than 1.7.0.” while I have Clojure 1.10.2 installed. Luckily I came across a Stack Overflow post that mentioned there being a version number inproject.clj. ↩ -

Do note there is at least one small difference between the code on GitHub and the code from the book. The GitHub code has

prompt-movecallingsuccessful-movefor valid moves and handling invalid moves itself. In the book,prompt-movecallsuser-entered-valid-moveoruser-entered-invalid-movefor valid and invalid moves respectively. This post uses the code from GitHub. ↩ -

Some functions, such as

println, returnnil, because they don’t really have anything to return. ↩ -

This code doesn’t make much sense, since how would it deal with the game ending? You’d either use recursion (like in the Clojure version) or classes (very not functional programming). ↩